The Impossible Equation: Why Range Planning Is More Art Than Science

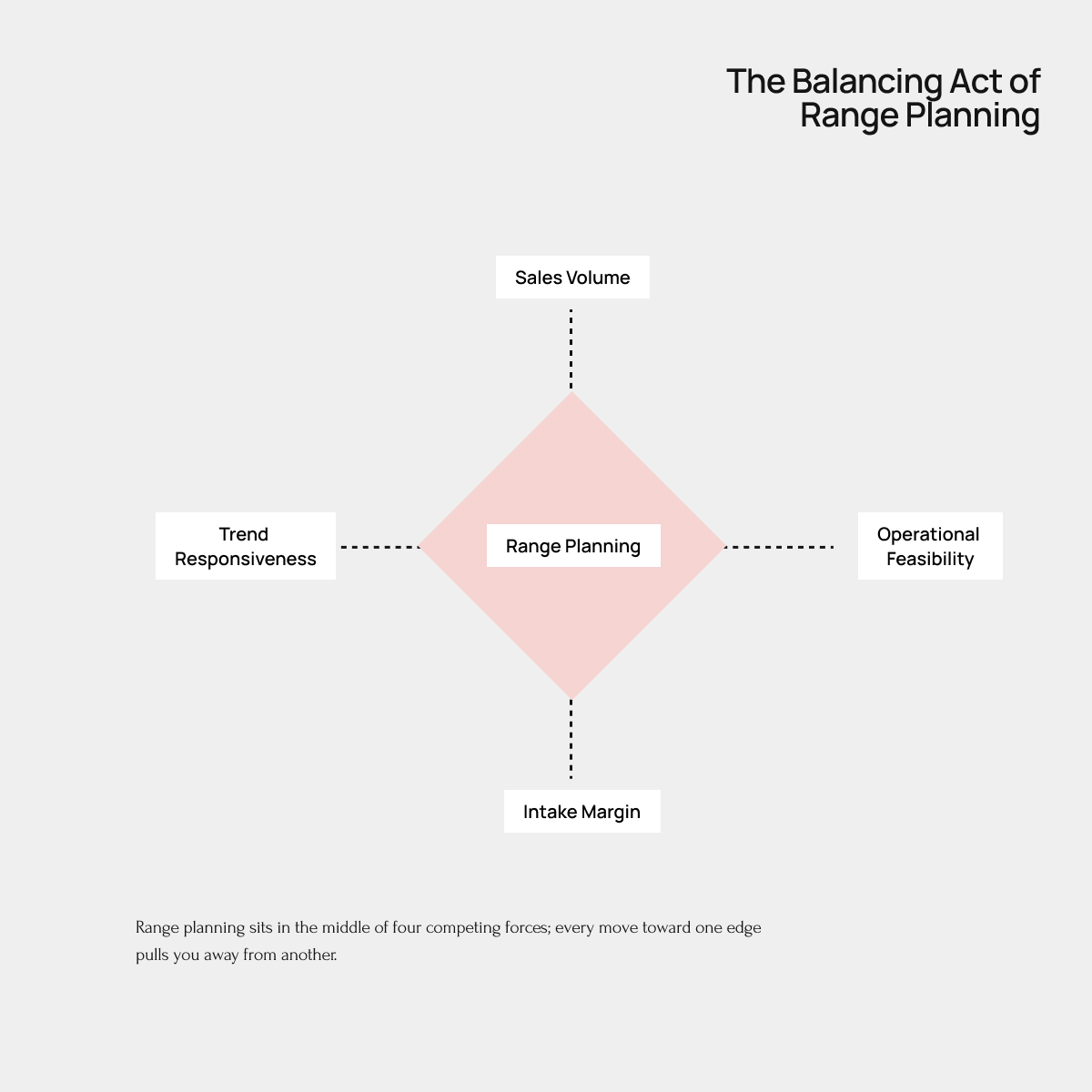

When rising prices, store constraints, and unpredictable trends collide, range planning becomes less about precision, more about instinct.

You plan for 80% sell-through. You hope for 90%. And you pray the last 10% doesn’t tank your margin.

It’s the merchandiser’s paradox: if you only ever bought what you knew would sell, you’d never have anything left to discount. If you bought only what your data told you to, you’d miss the trend-led moments that drive PR and hype. And if you tried to sell 100% of everything, you’d probably go broke trying.

This is the reality of range planning today. And it’s less science, more art.

The fantasy of 100% sell-through

There’s a reason even the best planners don’t aim to sell everything they buy.

Some of it’s about logistics. Some of it’s about channel conflict. But most of it is just... hard to predict. Sizing distribution, for example, is never going to be perfect. You’ll always end up with too many mediums or not enough extra-larges.

And the moment you scatter inventory across dozens of stores, warehouses, and regions, that 80% sell-through plan starts to look wildly optimistic. Factor in shifting trends, celebrity influence, and the weather, and your spreadsheet might as well be a horoscope.

In other words: you’re not failing. The system’s built that way.

Demand planning isn’t data-driven… it’s data-informed

A lot gets said about predictive analytics in buying and merchandising. But most range plans still come down to a blend of:

historical sales of similar styles ("this coat sold well last autumn")

adjacent trends ("this shade of pink is having a moment")

gut instinct ("this feels like something our customer would wear")

Some of that can be modelled. Most of it can’t. And that’s before you get to things like stock availability, fabric lead times, or how many similar items are already on the shop floor.

Which is why it’s rare that anyone buys to sell 100%. Most brands budget for an 80% sell-through, knowing full well that the other 20% is just the cost of playing the game.

Pricing vs volume: the impossible trade-off

The margin conversation starts long before the first unit sells. It begins with pricing.

Take this example: you brief 10 dresses. Five need to come in under £200. Three can hit the £300 mark. One can stretch to £500, as long as it’s special enough to justify the tag.

But when one of the £300 dresses comes back with a cost that pushes the RRP closer to £700, you have a decision to make: reduce your quantity and protect your intake margin, or take a hit and hope the volume offsets the lower markdown margin later.

There’s rarely a right answer. Just a lot of Excel.

Stores make everything harder

In an ideal world, all your inventory would sit in one place, ready to fulfil any order. That’s how DTC brands can push higher sell-through rates: centralised stock, minimal redistribution, and real-time visibility.

Retail networks, on the other hand, are chaotic.

You need to fill rails, even when the sales budgets don’t justify the stock. You need to cover multiple sizes, even when only three sell. And when something sells out in one city but not another, you’re on the hook for shipping, warehousing, and duties just to move things around.

At best, you get a higher sell-through rate. At worst, you end up with your best stock in the wrong city, too late to fix it.

Marketing loves the wrong products

Ask any merchandiser which products get all the ad spend, and they’ll tell you: the ones you have the least stock of.

Marketing and buying often operate on different calendars. While merch is focused on margin and volume, marketing is chasing trends, stories, and campaign visuals. That means the loudest product in your lookbook is often the one you bought in the lowest volume.

This disconnect isn’t just frustrating, it’s costly. But some brands are closing the gap. At one of the biggest Scandinavian fashion brands we work with, for example, merch, marketing, and store GMs would align early on which products were the heroes, then back them with volume buys and proper marketing muscle.

Get it right, and you create a self-fulfilling sell-through story. Get it wrong, and you’re left with rails full of quiet sellers and campaigns that convert to out-of-stock pages.

So what does good range planning look like?

You won’t solve the equation. But you can get better at managing the variables:

Align your marketing and merch calendars earlier

Know which products you want to sell out of (and which you never want to)

Understand where you can afford to protect margin, and where you can’t

Design range plans that account for channels, not just SKUs

Assume you’ll get some of it wrong, and build flexibility into your plan

Final thought: buy everything you can sell, and sell everything you can buy

That’s the principle that gets lost somewhere between merchandising and margin meetings. It sounds simple. But when you factor in channel complexity, trend cycles, pricing shifts, and fulfilment friction, it becomes, in the best and worst sense of the word, an art form.

You’ll never sell it all. But you can get closer. Just don’t expect a formula to get you there.