Tackling Football's Sustainability Issue

Without tackling sustainability, should football's growth continue to accelerate?

Football is the biggest sport in the world. And it has a complex relationship with sustainability.

In this piece, we unpack the commercial growth of the beautiful game and shine a light on its sustainability dilemma, focusing on an area currently under little scrutiny—merchandise.

Thanks to its cross-cultural positioning and the enormity of its fanbase, football’s sustainability issue is multi-faceted.

As global demand for football accelerates, so does the scale of business conducted. With this comes increased travel-related emissions between domestic and international games, a sharp rise in record-breaking sales and many clubs being put at financial risk as they chase the commercial riches of promotion and qualification for major tournaments (e.g. Champions League).

With more eyes on the game comes a considerable rise in demand for merchandise, resulting in increased production - particularly of non-biodegradable products that inevitably end up in landfills. This highlights a series of unsustainable models that need rethinking.

Scale

Football’s popularity continues to peak, and its revenues are at an all-time high.

Already boasting ~4.2 Billion fans globally, growing interest in national and international tournaments like the Premier League, Bundesliga, La Liga, FIFA World Cup, Euros, and AFCON, alongside the acceleration of the Women’s game, is set to see this figure soar further.

Ignoring for a moment the concentration of money at the elite level and the jeopardy this is causing down the football pyramid (another one of football’s sustainability challenges), the commercial growth of football globally is a breakout success.

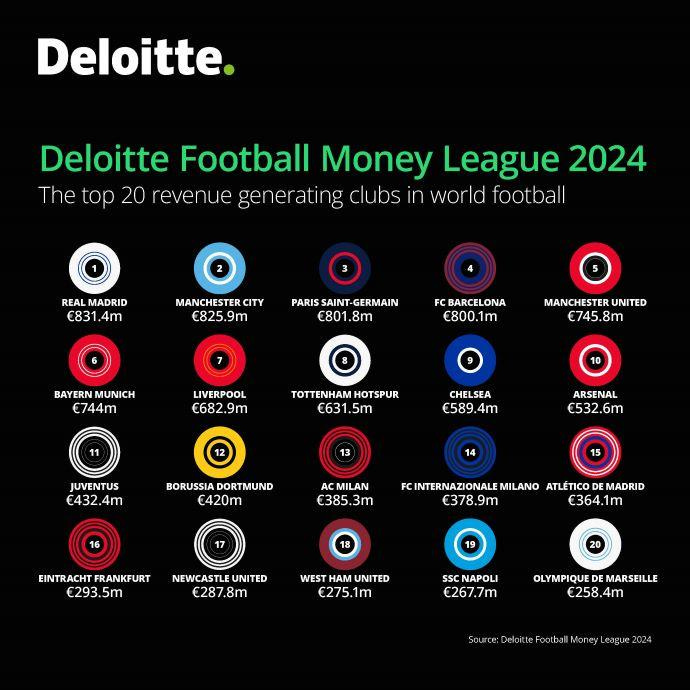

There has been a 14% increase in YoY revenue generated by the top 20 clubs in the 2022/23 season (as highlighted by the 27th edition of the Deloitte Football Money League).

Increased global demand has resulted in a series of lucrative TV deals: NBC striking a $2.7billion streaming deal with the Premier League until 2028, attributed to the league’s interest growing 53% in the US since 2020,

A new broadcasting deal between Sky and the Premier League was closed at £6.7billion in the UK.

The FIFA World Cup in Qatar 2022 reached an estimated audience of five billion, including a cumulative total of 3.4 million live spectators.

In the last seven years, we’ve witnessed the ten most expensive transfer fees, the biggest kit deal, and the most expensive takeover in Premier League history.

While these figures speak to massive commercial success, they obscure a challenge for clubs increasingly producing, selling, and shipping merchandise to an expanding global market. Is it sustainable and responsible?

Demand for product

A larger, more geographically dispersed consumer base boosts merchandise and replica kit demand.

Most teams launch three kits per season: home, away, and third.

Despite many kits – particularly home strips – baring minor variation between seasons, teams continue to work with manufacturers on a per-season cadence as the jerseys sold to fans are vital drivers of retail revenues generated by clubs, with the world’s biggest teams selling millions of units per year.

Alongside the replica kits, several pre-match, training, and lifestyle collections launch throughout the season—you can expect ~10 apparel drops per season from major teams.

To put this into context, since 2012, Premier League clubs have collectively released 600 kits, with the “Big Six” teams alone responsible for 168.

Albeit the sheer frequency of releases, demand remains high. During the 2022/23, the eight biggest European teams (including Real Madrid, Barcelona F.C. and Bayern Munich) alone sold over ~11million shirts—a number massively eclipsed when factoring in all 76 teams that make up the top four European leagues.

Ensuring they meet global demand, teams employ a combination of channels to reach consumers, including retail partners (Nike, adidas, Sports Direct, JD Sports, et cetera), dedicated club stores in stadiums, home cities, and local airports, and direct-to-consumer through apps and online stores.

Production and supply chain.

A sizeable chink in the sustainability of football teams’ supply chain comes from one of the most, if not the most, recognisable parts of a club; its kits.

Seasonal kit releases are big business for major sports manufacturers. In 2023, Manchester United and adidas closed a Premier League-record-breaking £900million kit deal, while in 2019, Real Madrid and adidas, and Manchester City and PUMA reached agreements of £946million and £650million, respectively.

Furthermore, an upcoming extension to the contract between Nike and Liverpool F.C., which expires in 2025, is expected to be worth upwards of £100million per year.

These eye-watering figures don’t include merchandising, which significantly bolsters the value of such deals.

In 2022, adidas attributed a double-digital revenue growth rate in its ‘Performance’ category to an exceptional increase in football-related sales. Nike made over $1.5billion in the football category alone in 2021.

As the value and contract length of deals between teams and manufacturers continue to grow in line with football-related sales, increased kit production has led to a growth in the use of sustainable fabrics amid manufacturers’ sustainability pledges.

For example, PUMA says it: “believes in integrating sustainability into every aspect of our manufacturing processes for all products” and uses 100% recycled materials (excluding trims & decorations) in football shirt production.

While adidas utilises 100% recycled polyester doubleknit, Nike uses recycled polyester made from recycled plastic bottles to produce a large majority of its shirts, in line with its Move to Zero commitments.

Despite these use cases, most manufacturers, on which most major clubs rely, have yet to make any real sustainability commitments specific to kit manufacture beyond the use of materials that fall under their existing, generalised pledges. After all, sustainable fibres alone have little effect when tens of millions of shirts are produced and sold annually.

With production levels so high, product end-of-life must be considered. While several manufacturers have committed to using or working towards 100% recycled materials in kit production, dedicated end-of-life uses or recycling methods aren’t offered to consumers.

At the end of a season, most unsold kits are offloaded to third-party retailers or outlets, offering consumers a significantly reduced buy-in; however, football shirts aren’t currently biodegradable, meaning many will end up in landfill sites unless re-used by charitable organisations like KitAid.

With clubs so heavily reliant on their manufacturing partners to produce their kits, they lack operational influence on third-party supply chains, especially when manufacturers like adidas and Nike hold deals with various clubs across domestic and international leagues with differing sustainability commitments.

Although in-house production would make it easier for clubs to tune their focus to sustainability and transparency within the supply chain, matching the scale of demand that football’s growth has achieved is difficult. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t exceptions.

Transparency.

Outside of recycled materials used in kit production, sustainability and transparency within most teams’ supply chains are prescribed little focus.

This thinking is changing, however, as many teams have begun making a committed, transparent effort to report their carbon footprint to meet sustainability reporting requirements and demonstrate reductions towards achieving net zero—a crucial part of the English Football Association’s five-year sustainability strategy titled “Playing for the Future.”

Within the Premier League, Tottenham Hotspur – ranked the league’s greenest club for the 4th consecutive year – is amongst a list, including Manchester City and Liverpool, that have voluntarily provided reporting on emissions from a myriad of categories, including use of sold products, end-of-life treatment of sold products specifically.

For English Football League 2 side Forest Green Rovers, transparency sits at the core of its operation, including kit manufacture, earning it the title “greenest football club in the world” from FIFA in 2017.

The club, which went climate-neutral in 2017, launched the world’s first bamboo kit in 2021, which remains in circulation for the current season.

FGR’s recognition and tackling of football kit production and release cadence’s impact on sustainability has set a high standard yet to be replicated.

Liverpool F.C’s use of sustainable materials in its kits since the 2020/21 season has been highlighted by the club and in the press, thanks to Nike’s Move to Zero initiative—it’s important to note, however, that this applies to most Swoosh-partnered clubs and national teams, except Galatasaray.

An effort to make clubs more transparent has been made, with Chelsea F.C. and Arsenal among the teams outlining the environmental, social, and economic strategies they’re implementing to lower emissions, yet fall short of giving specific focus to their kit production and distribution supply chain.

Implementing change for the future.

If football’s growth trend is to continue, its relationship with sustainability must change.

Thanks to the commitments made by sporting bodies and associations that have trickled down to club level, there has been an uptake in transparent reporting on carbon emissions and what strategies have been implemented to tackle them.

As it currently stands, however, the kit supply chain hasn’t come under enough scrutiny, and as a result, little has changed concerning the sport’s sustainability dilemma.

Simply relying on manufacturing partners to use recyclable or recycled materials in production isn’t enough. As it currently stands, the number of kits produced per season is at a level unsustainable for the future of the sport.

On top of the environmental concerns, the cost of kits rising at a near-annual cadence, coupled with the current high-frequency release schedule, is creating an unsustainable market for fans.

Big ideas.

Thinking quixotically, clubs could bring manufacturing in-house to offer transparency throughout the supply chain while considering use cases for end-life products, such as trading in or recycling pre-loved kits for credit or a new product.

Alternatively, should they continue to work with partners like Nike or adidas, clubs should work towards ensuring all products across lifestyle, pre-match, and training, not just replica kits, are made from sustainable fibres. And the supply chains behind these items are fully transparent to consumers, driving up levels of accountability for ethical and environmentally friendly production practices.

Better yet, clubs could endeavour to reduce their product release frequencies through fan engagement—beloved stripes, either vintage or contemporary, could be used for multiple seasons. Why not maintain an iconic home and away shirt across several seasons, with the third kit reserved for fashion collaborations or special editions?

Financially speaking, the current supply chain works perfectly for clubs. The revenue generated per season speaks for itself, but for teams and the sport (as a whole) to operate sustainably in the future, profit cannot be the sole priority.

Football’s cultural dominance will undoubtedly continue to grow, as will global demand for merchandise and kits—but without prioritising and improving its relationship with sustainability, the environmental consequences of this growth leave a stain on the sport.